Is He Beefing With Abraham Lincoln

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/f8/04f87473-9755-43d4-a3d3-1c5b7d50941e/march-2015-booth-revolver4.jpg)

Every April fourteen, on the hour of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the place where information technology happened is i of the loneliest historical sites in America.

I should know. I've been making disappointing ceremony pilgrimages to the scene for more than than a quarter of a century. My first was in 1987, during my outset spring in Washington, D.C., when my hereafter wife and I were serving in the Reagan administration. After piece of work, we walked to the so-seedy neighborhood surrounding Ford'south Theatre and discovered Geraldine's Firm of Beef, a restaurant whose only allure was a table near the front window that offered a clear view of Ford'southward facade on Tenth Street NW. We decided to have dinner while we waited to see what would happen. Of course, nosotros thought, a crowd would get in presently to honor the most beloved president in American history. No doubt the National Park Service, which has administered Ford's since 1933, would hold a solemn ceremony.

Nine p.m., nothing. Ten p.m.—nearly 20 minutes before the moment John Wilkes Booth fired his single-shot Deringer pistol at the back of the president's head and changed the nation's destiny—nothing. So we saw movement. A station wagon turned onto Tenth Street. In it was a picture-postcard American family unit—ii parents and two young children, a male child and a daughter. As the car slowed and coasted past, the driver pointed out the window to the theater. The kids' heads swiveled to their left and nodded up and down. The motorcar drove on.

That was it. That was how the American people honored Abraham Lincoln on the night and at the place of his assassination. I did not realize information technology so, but that was the moment that would lead me to write my book Manhunt: The 12-Solar day Hunt for Lincoln's Killer.

On all the April 14ths that followed, nothing changed at Ford's. Far from inviting people to sit down vigil, the National Park Service's security guards and police force discouraged nighttime anniversary visitors. In 2013, I almost got arrested trying to honor Lincoln.

Around nine p.m. I sat, equally had become my habit, on the front steps of the Petersen Firm, the boardinghouse where Lincoln died at 7:22 a.m. on Apr 15, 1865. It, likewise, is administered by the National Park Service as function of the bump-off historical site. I imagined the theater doors across the way bursting open and the shouting, frenzied audience of i,500 flooding Tenth Street. I could see in my mind's middle the unconscious president as he was carried into the street. I pictured how a Petersen Business firm resident opened the door at the top of the staircase and shouted, "Bring him in here!" and how the soldiers carried him by the very spot where I saturday.

Across the street, a guard within Ford's Theatre pushed open a plexiglass door side by side to her security desk-bound and bellowed: "Get off those steps! Y'all can't sit down there. That'south private holding. I'll phone call the police." I got upward and crossed the street. I explained to her that tonight was the anniversary of Lincoln'south bump-off. That I served on the advisory quango of the Ford's Theatre Society. That I had written a book about what had happened. And those steps, I couldn't resist reminding her, belonged to the American people.

She gaped at me, uncomprehending. I returned to the Petersen House and sat down. Ten minutes afterwards, ii park service law cars pulled upwards. The three cops said that Officer Johnson had reported a hostile homeless man lurking about. "Lots of men sit on these steps and urinate on the house," said 1 of the officers. "How do nosotros know you're not going to do that? You've got no right to sit here." After much tense word, another officer rolled his eyes and advised me to enjoy the evening.

Last year, I brought two friends along as reinforcements. The land was in the heart of celebrating the 2011-15 Ceremonious State of war sesquicentennial. Surely that would bring people out. But no. Fewer than 10 people showed up. I posted a disappointed report on Twitter. And received no comments.

Things promise to exist different this April 14, the 150th anniversary of the bump-off. The Ford's Theatre Society and the park service will transform Tenth Street into a fourth dimension tunnel that will transport visitors back to the sights and sounds of 1865. Starting the morn of April 14, the street will be closed to traffic. Ford'due south will stay open for 36 hours directly to accommodate a schedule of brusque history plays, readings, musical performances and moments of silence. Street vendors will militarist pocket-size paper flags celebrating the fall of Richmond and the effective end of the Civil War, just equally they did in 1865, right up to the moment of the bump-off.

And at x:20 p.m., all will become silent, until a bugler playing taps breaks the spell. And then, for the first time in 150 years, mourners will hold a torchlight vigil in front of the Petersen House. I will exist at that place too, marking the climax of a lifelong fascination with the bump-off of Abraham Lincoln.

I was born on February 12, Lincoln'due south birthday. From childhood, I received books and souvenirs about him as gifts. When I was 10, my grandmother presented me with an engraving of Booth's Deringer. Framed with it was a clipping cutting from the Chicago Tribune the twenty-four hours Lincoln died. Merely the story was incomplete, ending in mid-sentence. I hung information technology on my bedroom wall and reread it hundreds of times during my babyhood, often thinking, "I want to know the rest of the story." I still accept information technology today.

On weekends I begged my parents to accept me to the erstwhile Chicago Historical Society and so I could visit its most prized relic, Lincoln's deathbed. I longed to become to Washington to visit Ford'due south Theatre, and my father took me with him on a business organisation trip there. That boyhood curiosity turned me into an obsessive lifelong collector of original Lincoln assassination documents, photographs and artifacts.

And years later, it led to the books: Manhunt; its sequel, Bloody Crimes; and even a book for young adults, Chasing Lincoln'due south Killer. I could not have written them without my personal archive. In fact, I think of myself as a crazed collector who happens to write books. My drove contains magical objects that resonate with meaning. They don't only reflect history; they are history. For the 150th anniversary, I've picked out my favorite Lincoln assassination relics—from my collection and others—that best bring alive what Walt Whitman chosen that "moody, tearful night."

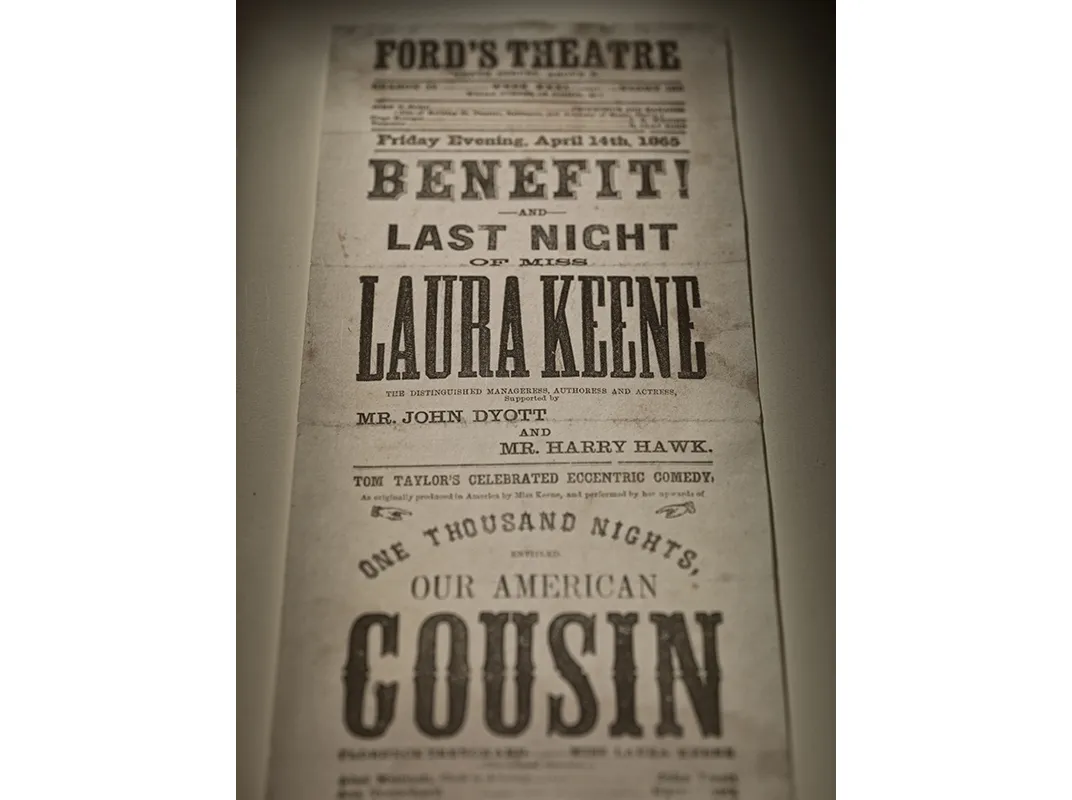

Ford's Theatre Playbill

On the morning of Friday, Apr 14, 1865, Mary Lincoln notified Ford'southward Theatre that she and the president would attend that night's performance ofOur American Cousin. That pleased Laura Keene. The evidence was a "do good" for the star actress; she would share in the profits, which would presumably grow every bit word of the commencement couple's plans spread. A few blocks away, on D Street near Seventh, H. Polkinhorn & Son printed a playbill—something to hand out on the street that day to drum upwardly ticket sales. Just that night's events invested this common-identify slice of theatrical ephemera with unparalleled significance: It freezes a snapshot of the "before."

For me, the playbill conjures the opening scenes from one of Lincoln'southward happiest nights: the presidential carriage arriving on 10th Street, and inside the theater the sound of cheers, "Hail to the Chief," laughter and hissing gaslights. It besides resonates with eerie foreboding, symbolizing not but Lincoln'southward expiry, merely also the cease of Ford's Theatre, which would get nighttime for more than a century. Lincoln loved theater, and coming to Ford's. Whenever I leave my house to go there, where I often attend performances and other events, I always glance at the playbill hanging in my hallway. It reminds me that Ford'south is non simply a identify of death. Lincoln laughed at that place, too.

Lincoln'due south Top Hat and Overcoat

Zero from the president's wardrobe more potently symbolizes his identity than his top lid. Lincoln adopted ane every bit his trademark back in Illinois, when he was a lawyer, long before he came to Washington. He chose unusually tall hats to attract attention and accentuate his height. At 6-foot-4, Lincoln already towered over virtually of his contemporaries; his hat made him look like a seven-foot giant. This is the hat that he wore on Apr fourteen, and that he doffed when he stood in the President'southward Box at Ford'southward and bowed to admit the jubilant audience of his boyfriend citizens.

Lincoln'south signature color was black, and throughout his presidency he wore a white shirt, black pants and a thigh-length frock coat. And the night he went to Ford'southward Theatre, he wore a custom-made blackness wool Brooks Brothers overcoat trimmed at the neckband, lapels and cuffs with grosgrain piping. The black silk quilted lining was stitched with the outline of a big American eagle, a shield of stars and stripes and the motto "One Country, One Destiny." How eerily appropriate that when Lincoln was murdered, his body was draped in a garment writ large with the words for which he gave his life.

Swatch of Laura Keene's Costume

Later on Booth fled Ford'south, Laura Keene raced from the stage to the President's Box, where she discovered that Dr. Charles Leale had laid Lincoln on the floor. She knelt beside the unconscious, dying president and cradled his head in her lap. Blood and brain matter oozed from the bullet wound onto her silken costume, staining its festive ruby-red, yellow, green and blue floral pattern. Like a Victorian bride who lovingly preserved her wedding dress, Keene cherished her frock from this terrible night. But information technology presently became an object of morbid curiosity—strangers tried to cutting swatches equally gruesome keepsakes—and she eventually exiled the haunted relic into her family'southward care. The wearing apparel vanished long ago, but miraculously five swatches survived. For more than a century, they take been legendary amongst collectors. The whereabouts of this case had been unknown until it surfaced in the late 1990s, and I acquired it. This one, co-ordinate to an accompanying letter of provenance from Keene's grandson, was presented to a longtime family unit friend. The gay floral blueprint remains almost as bright as the day the apparel was made more than 150 years ago in Chicago past dressmaker Jamie Bullock. But the red bloodstains faded long agone to a pale rust-dark-brown.

When I was working onManhunt, I never let this swatch out of my sight while I wrote the scene describing what happened in the President's Box afterwards the shooting. As I stared at this blood relic, I saw it all, and the paragraphs wrote themselves.

Lincoln's Deathbed

At 7:22 and x seconds a.thou. on April 15, after an all-night vigil, Abraham Lincoln died in a back room at the Petersen House on a bed that was as well small-scale for his frame. The doctors had had to lay him diagonally atop the mattress. Soldiers wrapped his naked torso in an American flag and put him into a apparently pine box—a rectangular military machine crate. Lincoln, the sometime runway-splitter, would not take minded so simple a coffin. After they took him habitation to the White Firm, sheets, pillows, towels and a coverlet lay on the boardinghouse bed, still moisture with the president'due south claret. Ii Petersen Business firm boarders, brothers Henry and Julius Ulke, 1 a photographer and the other an creative person, set a tripod photographic camera and, with the morning sun flooding the hallway from the front door all the manner back to the little rear room, photographed the scene.

Lock of Lincoln's Pilus

Within an hour after the assassination, Mary Lincoln summoned Mary Jane Welles to the Petersen Firm. Mary Jane, the wife of Navy Secretarial assistant Gideon Welles, was one of Mary's few friends in Washington. They had bonded over shared sadness: In 1862, Mary Jane had helped nurse 11-year-old Willie Lincoln until he died of typhoid fever; the side by side twelvemonth, the Welleses lost their three-twelvemonth-old son to diphtheria. On the morning of April 15, Lincoln's death room emptied of mourners (including Gideon Welles) save one: State of war Secretary Edwin M. Stanton, whom Lincoln called his "Mars, God of War." Stanton was an imperious and widely feared cabinet secretarial assistant, merely he had loved the president, and the bump-off was for him a profound personal tragedy. Lone with his fallen chief, Stanton cutting a generous lock of the president's hair and sealed it in a plainly white envelope. He knew who deserved the memento. Later signing his name on the envelope, he addressed it "For Mrs. Welles." When she received information technology subsequently that mean solar day, she inscribed the envelope in pencil in her own pocket-sized, bully hand: "Lock of Mr. Lincoln's hair Apr fifteen, 1865, Chiliad.J.W."

She mounted the lock in an oval gold frame, forth with dried flowers she nerveless from Lincoln's bury at the April 19 White House funeral. The carte du jour securing the relics in identify behind their glass cover was calligraphed to testify that they were "Sacred to the Memory of Abraham Lincoln 16th President of the Us." This isn't the simply surviving lock of Lincoln'southward hair. Mary Lincoln claimed 1, every bit did several of the doctors present at the Petersen House or his autopsy. Others were purloined from Lincoln's caput, and i wonders how he made it to the grave with any hair at all. But the Stanton/Welles lock, with its unparalleled provenance and interwoven tales of dear and loss, is mayhap the about evocative one of all.

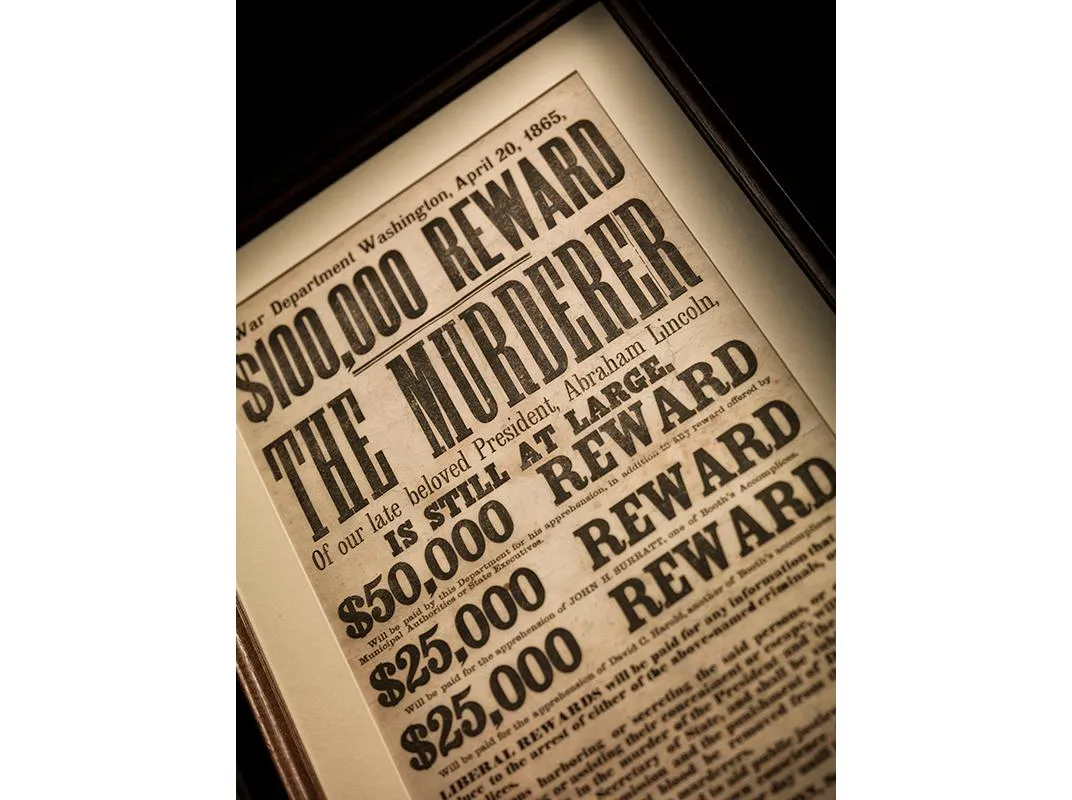

$100,000 Advantage Poster

Today, it is the most famous reward poster in American history. In 1865, it was the symbol of a failing, increasingly desperate manhunt. And when I was nineteen years erstwhile, it was my first of import acquisition. I had coveted i of these posters since I was 10, and when I was a sophomore at the University of Chicago I spotted i in a volume dealer's catalog and ordered information technology at in one case. I bought the poster instead of a used car.

Booth shot Lincoln in front of one,500 witnesses, escaped from Ford's Theatre, galloped away on a horse and vanished to parts unknown. The failure of several yard pursuers to hunt downwards Lincoln'southward assassin had go an embarrassment to the regime. On April xx, half dozen days after the bump-off, State of war Secretary Stanton proclaimed a $100,000 advantage for the capture of Booth and two of his alleged accomplices. It was a staggering sum—the average worker was earning about $1 a day—and the War Section printed broadsides to publicize it. Every penny of the blood money was paid, divided amid a few dozen of the pursuers most credited for the capture or decease of John Wilkes Booth and his accomplices.

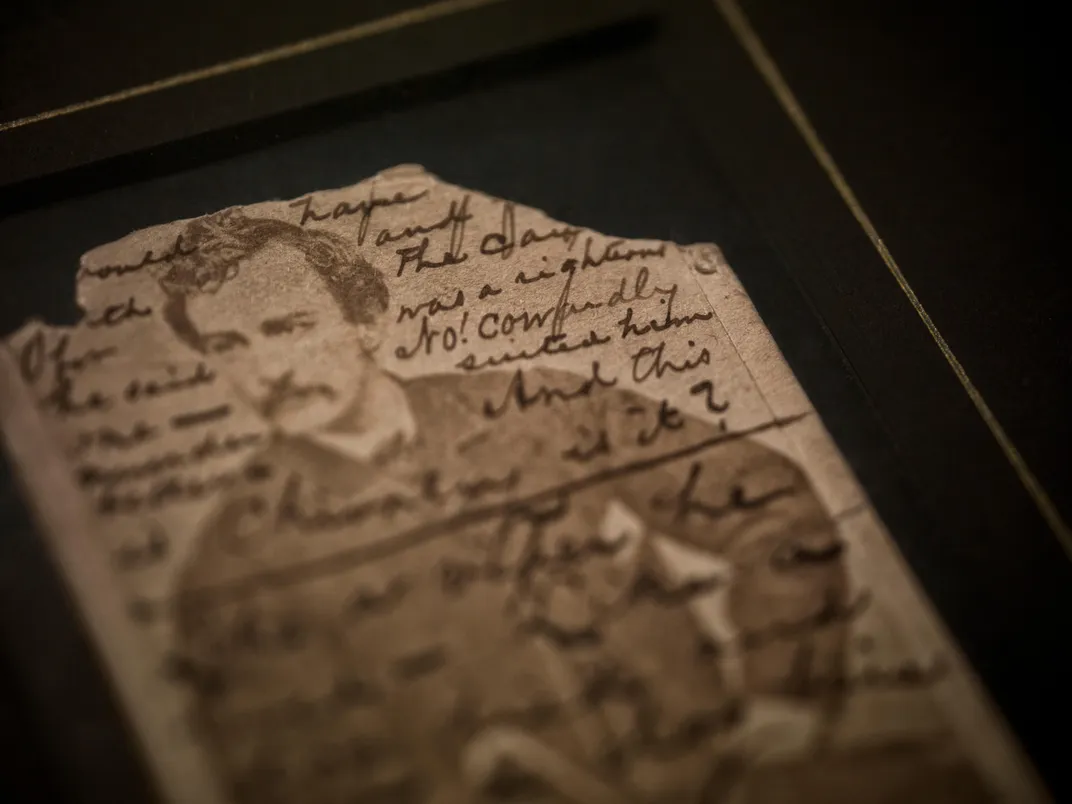

Defaced Photograph

The day afterward the assassination, technicians at the Surgeon Full general's photograph laboratory copied a popular carte-de-visite photo of Booth and printed multiple examples for distribution to the assassin's pursuers. This re-create was issued to William Bender Wilson, a telegraph operator at the State of war Section who was in the field during the manhunt. Wilson inscribed its provenance on the back of the menu: "This picture of J. Wilkes Booth was given to me from the War Department at Washington, D.C. whilst Booth was still a avoiding. Wm. B. Wilson." Upon learning of Booth's death, Wilson expressed his contempt for the murderer by defacing his prototype with a handwritten bulletin: "...for the cause he said was a righteous one. No! Cowardly murder suited him meliorate. And this is Knightly is information technology? Like a viper he lived—like a dog died, and like a dog buried. 'Assassin.' 'Booth the accursed.'" Few other relics preserve so well the passions unleashed in April 1865.

The Bullet That Killed Lincoln

Booth fired a lead ball at Lincoln's caput. The bullet entered below the president's left ear, bored diagonally through his brain and stopped behind his right eye. Lincoln never regained consciousness. No autopsy was necessary to decide the crusade of death, but it would take been obscene to bury the president of the United States with a bullet in his encephalon. Information technology had to be dug out. Edward Curtis, an assistant surgeon at the dissection, described the hideous piece of work: "I proceeded to open the head and remove the brain downwardly to the track of the brawl. Not finding it readily, we proceeded to remove the entire encephalon, when, as I was lifting the latter from the cavity of the skull, suddenly the bullet dropped out through my fingers and fell, breaking the solemn silence of the room with its clatter, into an empty basin that was continuing beneath. There information technology lay upon the white china, a little black mass no bigger than the end of my finger—ho-hum, motionless and harmless, nonetheless the crusade of such mighty changes in the globe's history as nosotros may perhaps never realize." Whenever I visit this bullet at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland, I hear its echo in the basin.

Berth'southward Arsenal

Booth'due south Deringer is simply one of several artillery he purchased for his March 1865 plot to kidnap the president and soon deployed in his plot to kill Lincoln. Booth had two Colt revolvers and a Spencer repeating carbine with him when he was killed. He had issued a revolver and knife to George Atzerodt, who was supposed to murder Vice President Andrew Johnson. (Atzerodt got boozer and ran away, throwing the bract into the street and selling the pistol at a Georgetown shop.) Berth lent a knife and Whitney revolver to Lewis Powell, who made a encarmine but failed effort to impale Secretary of State William Seward. (Powell bankrupt the pistol on the skull of one of Seward'due south sons and used the pocketknife to stab Seward nearly to death, along with several other members of his household.) Along with his Deringer, Berth carried into Ford'south Theatre a Rio Grande camp knife, which he used to stab Lincoln's invitee Maj. Henry Rathbone in the theater box, and which, later he leapt to the phase, he thrust above his head for all the audience to see as he shouted, "Sic semper tyrannis" ("Thus ever to tyrants"). The audience was also far away to read the mottoes acrid-etched onto the blood-smeared blade: "Land of the Free/Domicile of the Brave"; "Liberty/Independence." How strange that the president and his assassin both embraced those sentiments.

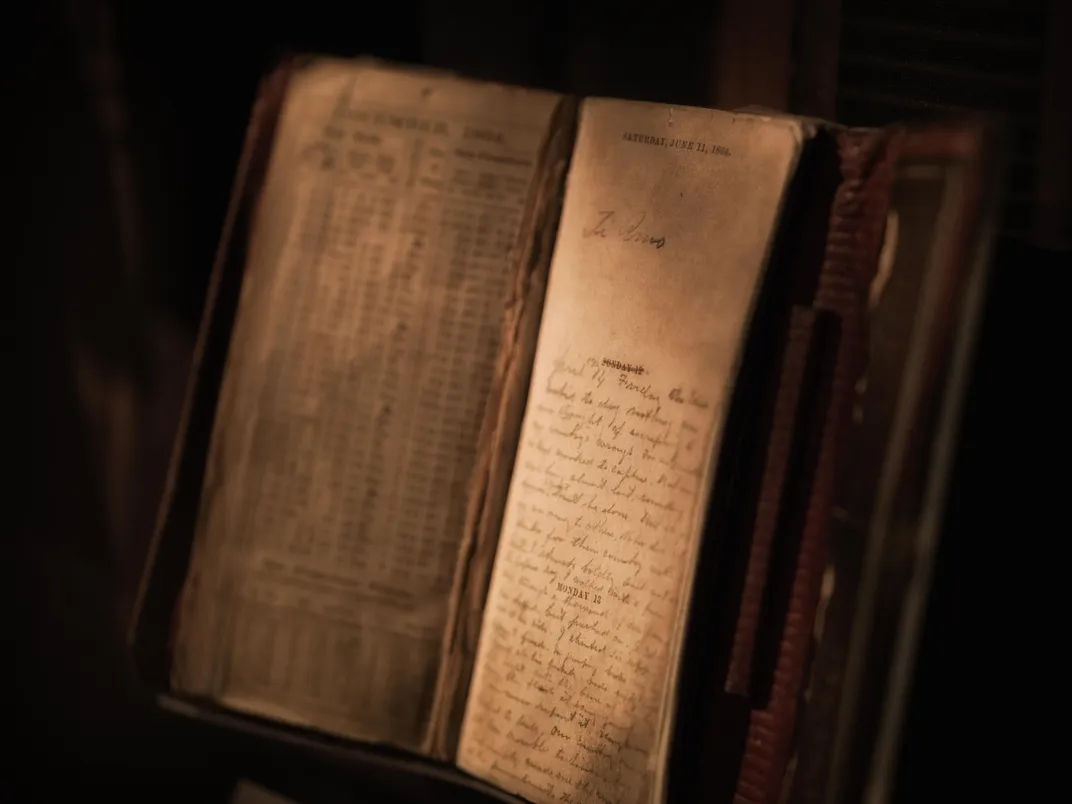

Booth'southward "Diary"

Opposite to popular belief, Booth never kept a "diary" of the Lincoln assassination. During the manhunt he carried a pocket-size bound pocket calendar for the yr 1864, which contained several blank pages, and on those sheets he wrote several notorious entries. To read them today is to meet the heed of the assassinator in all its passion, vanity and mirage: "Our state owed all her troubles to him, and God simply fabricated me the instrument of his punishment"; "After being hunted like a dog through swamps, woods and last night being chased by gun boats till I was forced to return moisture cold and starving, with every mans hand confronting me, I am here in despair"; "I am abandoned, with the curse of Cain upon me"; "I bless the entire world. Have never hated or wronged anyone. This last was not a wrong, unless God deems information technology and so." The notebook takes readers back to Berth's hiding places. Information technology is easy to hear his pencil scratching confronting paper as he scribbles his final thoughts. One tin can imagine the soldiers plundering it from his body and rifling through its pages in the firelight of the blazing tobacco barn, or State of war Secretarial assistant Stanton scrutinizing information technology for clues almost the assassination after it was brought back to Washington.

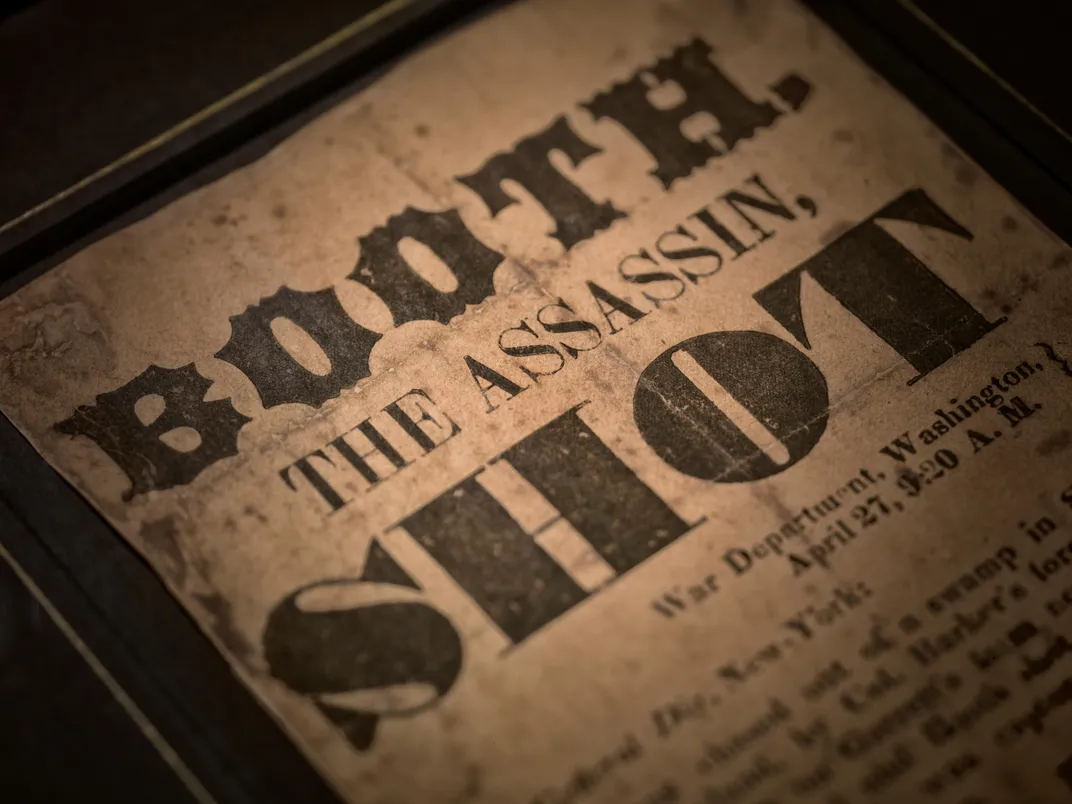

Broadside Announcing Booth's Expiry

After Booth died, at sunrise on April 26, Col. Everton Conger, one of the leaders of the patrol that had tracked him downwardly, rushed back to Washington to report to his superior, detective Lafayette Baker. Together, at most v:30 p.m., they went to Edwin Stanton'due south home to give him the news. "We have got Berth," Baker told him. The exhausted war secretary had no energy for grand linguistic communication or historical pronouncements. The statement he drafted, and which a War Department telegrapher transmitted beyond the nation, contained just the news that America had been waiting 12 days to hear. A broadside repeated the report:

Berth, THE Assassin, SHOT

War Department, Washington. Apr 27, nine:twenty A.1000.

Maj. Full general Dix, New-York:

Booth was chased out of a swamp in St. Mary's canton, Maryland,

by Col. Barker'south [i.e., Bakery] force, and took refuge in a barn on Garrett's farm, near Port Royal. The barn was fired and Booth shot and killed. His companion, Harrold [David Herold], was captured. Harrold and Berth's body are now here.

E.M. Stanton, Secretarial assistant of State of war.

When a unique example of this broadside, hitherto unknown, surfaced unheralded a decade ago at a small regional sale, I added it to my athenaeum. It is published here for the get-go fourth dimension.

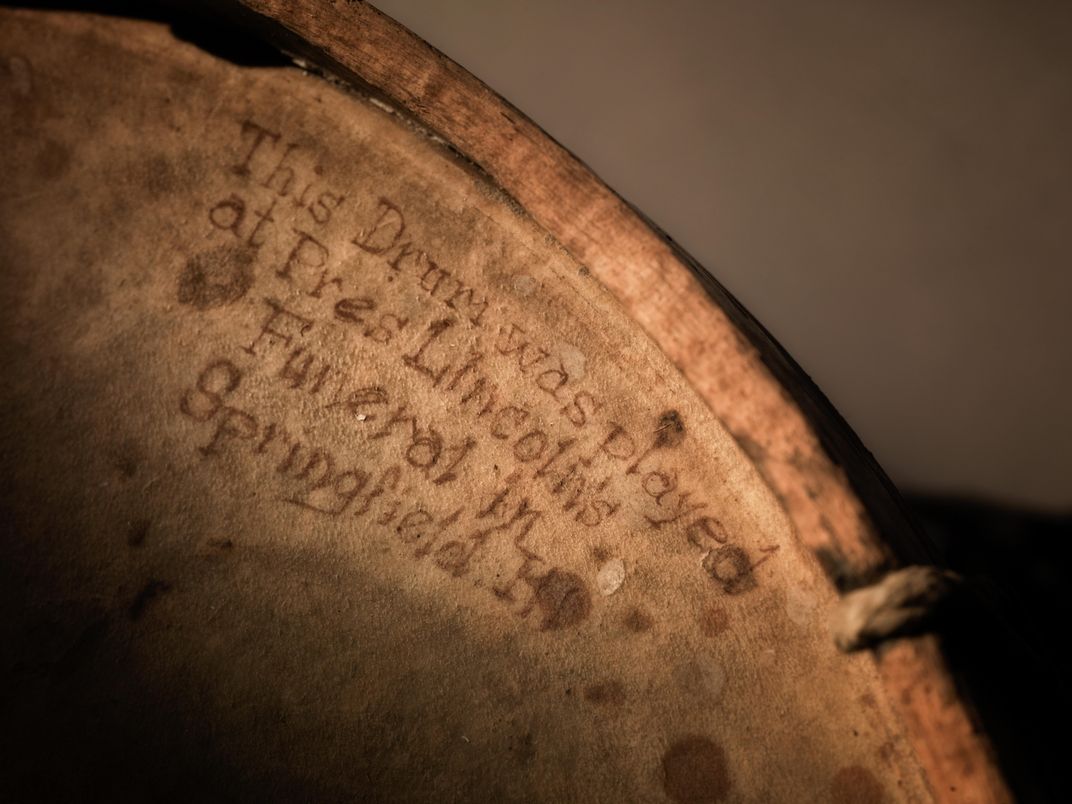

Mourning Pulsate

Abraham Lincoln's last journey began when soldiers placed his corpse aboard a special train that traveled the 1,600 miles from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois, over thirteen days. Ane 1000000 Americans viewed his corpse in the great cities of the North, and seven million people watched his funeral train laissez passer by. Whenever Lincoln'southward trunk was removed from the train for a public viewing, military units joined the procession, and the troops marched to the audio of massed drums. In Springfield, the corpse was displayed for 24 hours in an open catafalque at the State House, where Lincoln had served as a legislator and given his famous 1858 "Firm Divided" speech. And at eleven:30 a.m. on May iv, 1865, the drums beat one last time for Father Abraham as the funeral procession exited the State Business firm and passed Lincoln's quondam dwelling at Eighth and Jackson streets en road to Oak Ridge Cemetery.

One of those drums—a long-lost relic bearing a patina of dust and neglect—was recently discovered in Illinois. It is no different from thousands of military company drums manufactured during the Ceremonious War for apply by teenage drummer boys in an infantry company of one hundred men. It has a body of unpainted tulipwood or ash, calfskin heads, painted oak rims, hemp cords and leather pulls to arrange the tautness of the heads and the brightness of the audio. This one was made in Granville, Massachusetts, by Noble & Cooley, a business firm founded in 1854 and withal in concern today. Its oak rims have been beaten down from countless drumstick strikes—more than on any other Civil State of war drum I've e'er seen—and no marks indicate which regiment or company the drummer played for. Only a remnant of black mourning ribbon—a few inches from a gyre that must accept once laced the drum—still hangs from the lesser rim. And on the summit head, written in ink, is a remarkable history: "This Drum was Played at Pres Lincoln'southward Funeral in Springfield Sick." On the day I acquired it, I held a pair of Ceremonious War-era drumsticks in my hands and—conscientious non to damage the frail calfskin head—tapped out faintly the muffled audio of the funeral march.

Editor'south notation:This story initially said that Berth fired a one-ounce lead ball at Lincoln's head. While t he plaque beneath Berth'due south Deringer at the Ford's Theatre Museum lists the weight of the bullet as "nearly an ounce," the National Museum of Health and Medicine, where the bullet is displayed today, says information technology has no record of its weight and information technology cannot be weighed now because it has been permanently mounted. Bullets in the 1860s were not uniform. A f irearms expert at the National Museum of American History says 0.32 ounces is well within the realm of reason.

Manhunt: The 12-Mean solar day Chase for Lincoln'due south Killer

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-blood-relics-from-the-lincoln-assassination-180954331/

0 Response to "Is He Beefing With Abraham Lincoln"

Postar um comentário